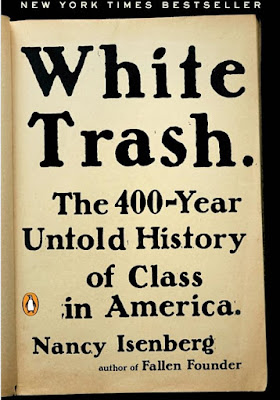

The book rose to prominence in the wake of Donald Trump's election, as if it were a Rosetta Stone for decoding the meaning of that event. Yet using class as a monocausal explanation for any such historical event is questionable, and the importance of the "white working class" in particular in electing Trump has been hotly debated since 2016. Sales of White Trash were undoubtedly boosted by this link, but this book would be an important one no matter who was elected president in 2016.

The title is slightly misleading because the book is not a complete exploration of America's class structure, but rather of the triangular relationship between elite white people, poor whites, and African Americans, and how this influences national politics. Isenberg comes as a mythbuster determined to destroy the legend of the American dream and equal opportunity for all, which is rather like exploding stationary clay pigeons once the evidence is marshaled. Certainly no student of American politics can fail to see all sorts of connections between the public image of a contemporary figure like Sarah Palin and all kinds of half-remembered figures Isenberg discusses, from Davy Crockett to Billy Carter.

I'm left with two major questions. On Isenberg's evidence, it's little better than wishful thinking to associate American founders such as Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson with the ideal of social equality. But is the persistence of this ideal in American politics and government only a hollow hypocrisy meant to legitimate the position of the elites? If so, why has it attracted such passionate devotion in America and around the world in the past two-and-a-half centuries?

The other issue, perhaps less important, has to do with the views Isenberg herself holds of poor whites. Are they merely victims of the white elites? Patsies who are willing to oppress their black brothers and sisters in exchange for not challenging the position of their white "superiors"? People with their own culture and history who accordingly deserve respect? It's puzzling to complete a major work such as this and be left with little idea of what the author thinks about its putative subject.

Five "Phoboses"

No comments:

Post a Comment